Visual Format Language for Autolayout

Other posts in the Autolayout series:

Visual Format Language (VFL) allows the concise building of your layout using an ASCII-art type format string. It’s a powerful tool, but above and beyond the official documentation, there isn’t a lot of information out there. This is going to be an entire post about a single method:

+ (NSArray *)constraintsWithVisualFormat:(NSString *)format

options:(NSLayoutFormatOptions)opts

metrics:(NSDictionary *)metrics

views:(NSDictionary *)views

(It’s quite a long method).

A quick diversion

When building a layout in code, all of your views must have translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints set to NO. This quickly becomes tedious. A quick category on UIView helps here:

@interface UIView (Autolayout)

+(id)autolayoutView;

@end

@implementation UIView (Autolayout)

+(id)autolayoutView

{

UIView *view = [self new];

view.translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = NO;

return view;

}

@end

There is much, much more in this category, which I will be covering in the final article in this series, together with a GitHub repository. For now, we just want the autolayoutView method.

This doesn’t work with views that require initialisation arguments (particularly a UICollectionView, or a UIButton, for those you’ll have to manually set the property) but does help in most cases. Remember, in an autolayout world, initWithFrame: is no more!

###views

This argument takes an NSDictionary, which contains each view referred to in the layout string. It can contain additional views as well, if you want to build a single dictionary for your entire view controller and re-use it in multiple calls. You’re likely to have at least two calls to constraintsWithVisualFormat when laying out a view controller, and may have several - each VFL statement represents layout along a single axis, in a single line.

For your convenience, a macro called NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings has also been created. You supply a list of view variable names, and it gives you a dictionary.

Because this was created specifically for NSLayoutConstraint, and indeed is declared in NSLayoutConstraint.h, there is a certain air of magic about it, like you must use this macro for your constraints. Of course this isn’t true. Above the definition of the macro it helpfully states:

NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings(v1, v2, v3) is equivalent to [NSDictionary dictionaryWithObjectsAndKeys:v1, @”v1”, v2, @”v2”, v3, @”v3”, nil];

In English, it creates a dictionary where the name of your variable is the key, and your variable is the object. For example:

UILabel *label = [UILabel autolayoutView];

NSDictionary *views = NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings(label);

[views objectForKey:@"label"] will return our label object, and [label] inside a VFL string will refer to the same object.

Some developers don’t create local variables when assigning views, putting everything directly into properties instead. This doesn’t work with the macro. In this case you can build the dictionary manually. You can use anything you like for the keys, as long as it matches what you use in the VFL string.

###metrics

This is another dictionary, and is a useful place to centralise any magic numbers you need for your layout. Like the views dictionary, you can include all the metrics you might use or re-use in multiple calls to this method. I’d recommend using a metrics dictionary over entering numbers directly in VFL, as it makes subsequent changes easier. It’s simple enough to do, particularly with Objective-C literals:

NSDictionary *metrics = @{@"buttonWidth":@200.0};

A simple dictionary with a string key and an NSNumber value. Using this dictionary as the metrics argument means that we can write buttonWidth in a VFL string and it will be automatically substituted with 200.0.

###options

The use of the options argument is is not explained clearly in the documentation. It states that you can only use a single one of the options, but this is not the case. For example, in a horizontal layout, it would be quite common to align the tops and bottoms of all of the views in the VFL statement. You can achieve this by passing in NSLayoutFormatAlignAllTop | NSLayoutFormatAlignAllBottom in the options. The values are bitmasks, and appear to be treated as such when processing. You can only apply options in the axis perpendicular to the layout you are using in the VFL string - so if you were doing a horizontal layout, you’d specify vertical sizing or positioning options such as NSLayoutFormatAlignAllTop or NSLayoutFormatAlignAllCenterY, and if you were doing a vertical layout, NSLayoutFormatAlignAllLeft or NSLayoutFormatAlignAllCenterX.

###format

This is the meat of the topic. I personally can’t make head or tail of the “Visual Format String Grammar” in the documentation, so here’s my attempt to explain it.

Views are named and enclosed in square brackets: [button] refers to the view stored under the key button in the views dictionary.

The superview is represented by a pipe : | character. All views must have been added to a superview before you can create constraints relating to layout. You will quickly be informed of this at run time if you don’t follow this rule.

Spacing is represented by a dash - character.

You don’t need to try and fit every facet of your layout into a single VFL string. All the method does is parse the VFL, make individual constraints and return them as an array. You have to be expressing at least one constraint though, otherwise the string is meaningless:

|-[button]-|: The button should be the standard spacing from the left and right edges of the superview.|-[button]: The button should be the standard spacing from the left edge of the superview.|[button]: The button should be flush to the left edge of the superview.-[button]-: Meaningless. Spacing to what?

Note that the second and third examples don’t appear to give the layout engine enough information to determine the width of the button - this is OK, because a button is smart enough to know its own width based on its title, image and font properties. The same applies for labels and many other built-in controls.

You gain more control over the layout by adding in metrics. Spacing metrics are added by adding in the metric and an additional dash:

|-30.0-[button]-30.0-|: The button should be 30.0 points inset from the left and right edges of the superview.

You can replace the number with a key from your metrics dictionary for reusability and DRY purposes:

|-spacing-[button]-spacing-|: The button should bespacingpoints inset from the left and right edges, wherespacingis a key in the metrics dictionary.

Sizing metrics are added by placing the number in parentheses after the name of the view:

[button(200.0)]: The button must be 200.0 points wide.

As before, this can be replaced with a key from the metrics dictionary:

[button(buttonWidth)]: The button must bebuttonWidthpoints wide, wherebuttonWidthis a key in the metrics dictionary.

Excitingly, it can also be replaced with the name of another view:

|-[button1(button2)]-[button2]-|: button1 must be the same width as button2, they have a standard spacing between them, button1 is a standard spacing from the left edge of the superview, and button2 is a standard spacing from the right edge of the superview.

This layout will divide the two buttons evenly across the width of the superview. This is useful on device rotation - your layout will grow or shrink to fit the different orientation.

All of these examples have dealt with horizontal layout, in a left-to-right fashion. For simplicity, I am assuming a left-to-right layout, but this will work for right-to-left layouts as well.

For vertical layouts, simply add V: to the start of the VFL string:

V:|-[button(50.0)]: the button must be 50.0 points high and the standard spacing from the top of the superview.

Here’s a practical example. We want three labels along the bottom of our view controller. The three labels must all be the same height and width, and must grow or shrink to fit as the device rotates.

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Create our three labels using the category method

UILabel *one = [UILabel autolayoutView];

UILabel *two = [UILabel autolayoutView];

UILabel *three = [UILabel autolayoutView];

// Put some content in there for illustrations

NSInteger labelNumber = 0;

for (UILabel *label in @[one,two,three])

{

label.backgroundColor = [UIColor redColor];

label.textAlignment = NSTextAlignmentCenter;

label.text = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%d",labelNumber++];

[self.view addSubview:label];

}

// Create the views and metrics dictionaries

NSDictionary *metrics = @{@"height":@50.0};

NSDictionary *views = NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings(one,two,three);

// Horizontal layout - note the options for aligning the top and bottom of all views

[self.view addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"|-[one(two)]-[two(three)]-[three]-|" options:NSLayoutFormatAlignAllTop | NSLayoutFormatAlignAllBottom metrics:metrics views:views]];

// Vertical layout - we only need one "column" of information because of the alignment options used when creating the horizontal layout

[self.view addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"V:[one(height)]-|" options:0 metrics:metrics views:views]];

}

We have defined the layout in just two VFL statements. Try that with manual frame setting and autoresizing masks.

So far, all of the examples described have had equalities expressed - that is, the button width must be 200. You can also use inequalities - these are arguably more useful on OS X than iOS, where users can’t go changing the size of your interface willy-nilly, but there are uses.

Inequalities are either less-than-or-equal-to (<=) or greater-than-or-equal-to (>=). This comes before the size metric in the VFL string. If you don’t include either, equality is assumed. If you want to be explicit, you can use == to signify equality:

V:|-(==padding)-[imageView]->=0-[button]-(==padding)-|:- The top of the image view must be

paddingpoints from the top of the superview - The bottom of the image view must be greater than or equal to 0 points from the top of the button

- The bottom of the button must be

paddingpoints from the bottom of the superview.

- The top of the image view must be

This would ensure that the superview can shrink to no more than the height of the padding, image and button, but if it grows larger than that, the image and button will move apart.

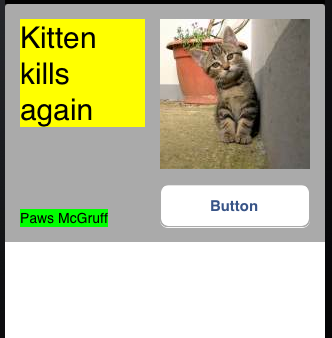

Consider this situation. We have a news article app, with a view that shows a headline, author, image and a button. The layout is like this:

The headline can be quite long - it can go over several lines. What do we need to think about for this layout to work?

- The header view is a fixed width.

- The header view must adjust its height to fit the contents.

- The headline’s bottom edge must be no less than zero points above the author information.

- The headline’s right edge must be inset from the left edge of the image.

- Headline text should wrap over multiple lines if required.

- If the headline’s length makes it longer than the height of the button and image together, the gap between the button and the image should grow.

- If the headline’s length makes it shorter than the height of the button and image together, the gap between the headline and the author information should grow.

In a pre-autolayout world, we’re looking at a world of tedious frame calculations and calls to font sizing methods. Welcome to the future:

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

UIView *headerView = [UIView autolayoutView];

headerView.backgroundColor = [UIColor lightGrayColor];

[self.view addSubview:headerView];

UILabel *headline = [UILabel autolayoutView];

headline.font = [UIFont systemFontOfSize:30.0];

headline.numberOfLines = 0;

headline.preferredMaxLayoutWidth = 125.0; // This is necessary to allow the label to use multi-line text properly

headline.backgroundColor = [UIColor yellowColor]; // So we can see the sizing

headline.text = @"Kitten kills again";

[headerView addSubview:headline];

UILabel *byline = [UILabel autolayoutView];

byline.font = [UIFont systemFontOfSize:14.0];

byline.backgroundColor = [UIColor greenColor]; // So we can see the sizing

byline.text = @"Paws McGruff";

[headerView addSubview:byline];

UIImageView *imageView = [UIImageView autolayoutView];

imageView.contentMode = UIViewContentModeScaleAspectFit;

[headerView addSubview:imageView];

// Lovely image loaded for example purposes

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(DISPATCH_QUEUE_PRIORITY_DEFAULT, 0), ^{

UIImage *kitten = [UIImage imageWithData:[NSData dataWithContentsOfURL:[NSURL URLWithString:@"http://placekitten.com/150/150"] options:0 error:nil]];

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_main_queue(), ^{

imageView.image = kitten;

});

});

UIButton *button = [UIButton buttonWithType:UIButtonTypeRoundedRect];

button.translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = NO;

[button setTitle:@"Button" forState:UIControlStateNormal];

[headerView addSubview:button];

// Layout

NSDictionary *views = NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings(headerView,headline,byline,imageView,button);

NSDictionary *metrics = @{@"imageEdge":@150.0,@"padding":@15.0};

// Header view fills the width of its superview

[self.view addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"|[headerView]|" options:0 metrics:metrics views:views]];

// Header view is pinned to the top of the superview

[self.view addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"V:|[headerView]" options:0 metrics:metrics views:views]];

// Headline and image horizontal layout

[headerView addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"|-padding-[headline]-padding-[imageView(imageEdge)]-padding-|" options:0 metrics:metrics views:views]];

// Headline and byline vertical layout - spacing at least zero between the two

[headerView addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"V:|-padding-[headline]->=0-[byline]-padding-|" options:NSLayoutFormatAlignAllLeft metrics:metrics views:views]];

// Image and button vertical layout - spacing at least 15 between the two

[headerView addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"V:|-padding-[imageView(imageEdge)]->=padding-[button]-padding-|" options:NSLayoutFormatAlignAllLeft | NSLayoutFormatAlignAllRight metrics:metrics views:views]];

}

Note that in the real app, you wouldn’t be setting the text and image values in this method, but in a separate setter method. I’ve just used examples here to keep the code simpler.

The resulting view looks like this:

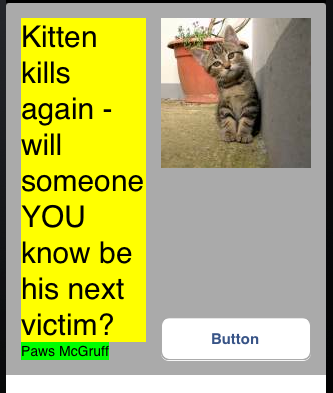

The editor thinks this isn’t lurid enough. Enter a longer headline, and without any other changes to the code:

For extra credit, if you call layoutIfNeeded inside an animation block in the setter method for your new headline, the headline view will animate to the new layout!

The last bit of finesse you can add to your VFL strings is the priority of the constraint. To be honest I haven’t had much use for priorities so far so I don’t really want to write too much about them. I think they are probably more useful for OS X. A priority is a float value between 0 and 1000. Apple recommend you use the values contained in the UILayoutPriority enum for readability and consistency. A constraint of priority 1000 (the default) must be satisfied - if you have conflicting constraints of the same priority, you’ll get run time warnings. Lower priority constraints will be set as close to their specified value as possible.

You add priorities to VFL strings using the @ character immediately after the value of the constraint:

"|[button(==200@750)]-[label]|": The button’s width should be 200 points, with a priority of 750."|-30.0@200-[label]": The label should be spaced 30 points from the left of the superview, with a priority of 200.

You can add priorities to the metrics dictionary if you want to use the enum values:

NSDictionary *metrics = @{@"lowPriority":@(UILayoutPriorityDefaultLow)};

[self.view addConstraints:[NSLayoutConstraint constraintsWithVisualFormat:@"|-30.0@lowPriority-[label]" options:0 metrics:metrics views:NSDictionaryOfVariableBindings(label)];

###Summary

We’ve dug further into the possibilities offered by VFL and expanded more on the details given in the official documentation, and there have been some real-life examples used. You can start to get really clever with VFL, building up the strings dynamically (e.g. iterating through an array of subviews) which gives you enormous flexibility.

However, there are still some limitations - you can’t use the multiplier part of constraints, which is great for setting fixed aspect ratios on views, and you can’t use it to link things like the centre of views to the centre of their superviews. To do that, you need to create individual constraints, which is the method I’ll be covering in the next part of this series. I’ll also be sharing some of the category methods I’ve developed to make common layout operations much less verbose.