Fun with scrollviews

iOS devices have small screens. Sometimes we want more content to be included on a screen and adding it to a scroll view is a great way of doing this. I’m going to look at the various numbers and measurements that a scroll view uses to do its job.

##How scrollviews work

A UIScrollView is a UIView subclass, so it has a frame which is, just as with any other UIView, the position and size of the scroll view in its superview.

The point of a scrollview is to contain one or more subviews, which are too big to fit inside the scrollview and still be completely visible. These subviews, when laid out and sized in the correct fashion, will fill an area the size of the scroll view’s contentSize. Each subview’s frame will be in the coordinate space of the scroll view’s bounds rectangle.

I’ll use an example to spell that out more clearly.

On an iPhone 5 the screen is 320 points wide. We want a carousel view with horizontal scrolling. Each image in the carousel will be 200 x 200 points. The first image view’s frame origin will be at (0,0) in the scroll view, the second will be at (200,0), the third at (400,0) - before any scrolling happens, this third view will be off the edge of the screen.

When scrolling happens, the frames of these subviews do not change. But as a great man once said, “And yet it moves”. What’s happening?

Scrolling affects the bounds of the scroll view. From the documentation for bounds:

On the screen, the bounds rectangle represents the same visible portion of the view as its frame rectangle. By default, the origin of the bounds rectangle is set to (0, 0) but you can change this value to display different portions of the view.

By changing the origin of the bounds of the scroll view, you display different parts of the content:

- Increasing the origin X moves the content left

- Decreasing the origin X moves the content right

- Increasing the origin Y moves the content up

- Decreasing the origin Y moves the content down

The size of the bounds rectangle remains the same as that of the frame, because the amount you can see is the same.

The subviews in the scroll view don’t know they are being moved. By scrolling, the user is moving a window around on top of the scroll view’s content view.

But of course, it gets more complicated

When scrolling programmatically or asking for the scroll view’s current scrolling position, we don’t work with the bounds origin. There is a contentOffset property instead, which is equivalent to the origin of the bounds rectangle. This is more obvious in intent than addressing the origin of the bounds directly.

Driving such features as pull-to-refresh and transparent navigation bars is the contentInsets property. This takes a UIEdgeInsets value which affects where the “natural” edges of the content are within the scroll view. It’s not immediately obvious what the implications of this property are, but I find it helpful to think of it as a way of setting where the bouncing effect of the scroll view is anchored:

The blue box represents the edges of the scroll view, the red box indicates the content insets.

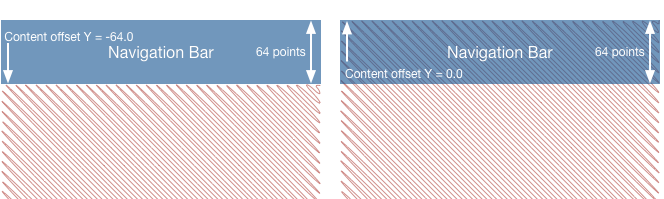

For example, take a standard app with a navigation bar and a scrollview. The scrollview extends behind the navigation bar and status bar, so the bounds rectangle is the full screen size, but when you pull down the content and release it to bounce, it bounces back to just underneath the navigation bar. This isn’t because the content starts 64 points down from the top of the scroll view, it’s because the scrollview has a contentInsets.top of 64. When the scrollview bounces to the top, it comes to rest with a content offset of -64.0 in the Y direction:

Pull-to-refresh controls work by adding additional values to the top content offset, to hold the scrollview content down while the indicator is showing the activity.

Learning by fiddling about

That is a whole lot of theory, and reading about scroll views isn’t the best way to understand the mechanics of them. I’ve made a demo project which allows you to see and adjust the numbers for a scroll view. I found it very useful when writing this article, hopefully it will aid your understanding as well. The demo project was used to generate the animated screenshot above.

UPDATE: I’ve amended the sample project to also list all the delegate calls that happen when scrolling occurs.

Further reading

objc.io has a great discussion of how scrollviews work. In summary, it all comes down to rectangles (doesn’t everything?). Ole Begemann has also written a fantastic overview.