It's not your fault

It’s quite telling that one of my highest voted Stack Overflow answers relates to nothing more than a simple misunderstanding of language. Apple’s use of the term fault in Core Data seems to cause quite a lot of confusion.

Apple to tend to use a ten-dollar word when a cheaper one will do in their APIs (ubiquity or segue, anyone?), but it’s usually a correct and unambiguous one. Fault, particularly when seen in a log statement, is all too readily interpreted as error.

There are three noun definitions for Fault:

- (noun) an unattractive or unsatisfactory feature, esp. in a piece of work or in a person’s character.

- (noun) responsibility for an accident or misfortune.

- (noun) an extended break in a body of rock, marked by the relative displacement and discontinuity of strata on either side of a particular surface.

None of these look useful.

Apple’s own definition says this:

A fault is a placeholder object that represents a managed object that has not yet been fully realized, or a collection object that represents a relationship.

Core data faults seems closest to the concept of Page Faults, so let’s assume that’s where the terminology comes from. I’d never heard of Page Faults before researching this article, but then I never went to computer school. I learnt to code on the streets.

Faults are what you get by default when you execute a fetch request. They take less memory than full managed objects. As soon as you request one of the properties of your managed object, the fault is seamlessly converted into a full object with all the properties you’d expect. This is called firing the fault, and is one of the many wonderful things core data does for you behind the scenes. Core Data will also convert managed objects back into faults if it sees fit. This allows you to hold large data sets in memory without having to worry too much about it.

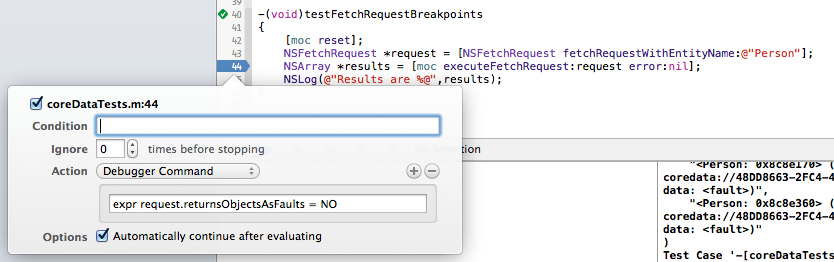

During debugging, depending on where you are in the code, you may try to log the value of a managed object and see the fault description in the console. This can be annoying if you want to check that a fetch request has returned specific objects. To get around this you can either access one of the object’s properties from the debugger (this will cause the fault to fire) or, to be a bit cleverer, set a breakpoint before your fetch is executed. In this breakpoint, you can run code to tell your fetch request to return full objects:

request.returnsObjectsAsFaults = NO;

With this breakpoint enabled, you’ll get the full data retreived. Turn it off, and you’ll get faults. Useful trick!

Reader @luka_bernardi points out another good way of firing a fault during debugging:

@richturton I use the trick `po [myListObj willAccessValueForKey:nil]` to fire the fault while debugging

— Luca Bernardi (@luka_bernardi) April 28, 2014He has this, and several other useful debugging commands, in this Gist.

Relationships are also faults when first requested.This makes sense because if you fetched every related object you’d run the risk of pulling the entire object graph into memory. You need a slightly different trick to examine these faults when debugging. If you try to print out the relationship as if it were a property of the object, or set the breakpoint as above, you get a “relationship fault” instead.

For quick and dirty debugging, you can access something on the relationship that will cause the data to be fetched - for example, if you had a Team object which had a members to-many relationship to a set of Person objects, you could type the following in the debugger:

p [team.members count]

This will fire the relationship fault and allow you to inspect the related objects (which will, of course, be faults themselves at this stage…). You can set an array of relationship key paths that will also be fetched at the same time as the original fetch. This can be a performance boost in your actual code if you always need to follow a relationship when using your objects. If you were fetching a table of Person objects and you wanted to show the details of the Team each person was in, you’d tell the fetch request to pre-fetch the relationship, since otherwise it would have to hit the persistent store every time, which is slower.

[request setRelationshipKeyPathsForPrefetching:@[@"team"]];

You can insert this code into a breakpoint using the same method as above if you just wanted it for debugging purposes.

Faults are Core Data’s way of keeping the memory use of your object graph down. They’re nothing to be afraid of, and they certainly don’t mean there’s an error in your code.